Imagine getting four hours of sleep in three days, jumping into freezing cold water with nothing but a speedo for hours on end, and lugging logs into the pacific surf at two in the morning. These actions are trademarks of the Navy Seal’s “Hell Week” training.

How do these individuals endure such mental agony and hardship? They are resilient.

Mental resilience is the process of effective adaptation in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant sources of stress. For years, governments and corporations have been trying to increase the resilience of their workforce. One company, Halo Neuroscience, has even created a brain zapping headset that is supposed to stimulate a person to the point of continued peak performance. The success of this and other similar devices are dubious as they do not demonstrate statistically significant increases in resilience.

So far, only one program has reported progressive milestones in increasing an individual’s resilience: the US Army’s Comprehensive Soldier Fitness Program (CSFP). The CSFP is a four pronged program aimed to increase soldiers’ mental resilience while decreasing their risk of suicide or PTSD:

- First prong: A mental resilience self-survey, known as the Global Assessment Tool (GAT), is used to asses soldiers’ current mental toughness

- Second prong: An individualized online program is made to help soldiers improve their mentally weak areas

- Third prong: Specific battalion leaders are taught an advanced form of resilience training through the Mental Resilience Training (MRT) program, and these resilience trainers are stationed in every battalion

- Fourth prong: Mandatory resilience training is implemented at every Army development school in the nation to test its effectiveness

The purpose of the CSFP is to equip soldiers with a durable mindset prior to conflict. The program is focused on preventing mental illness rather than treating soldiers after they have developed symptoms.

And so far it is working… we think.

The first part of the program, the GAT, has proven successful in analyzing soldiers’ emotional fitness (personal satisfaction and resilience), family fitness (how one functions in relationships), social fitness (how one interacts with their army community), and spiritual fitness (if one has a sense of purpose that extends beyond the self). Psychologists who are not funded by the military, such as University of Michigan’s Christopher Peterson, also suggest that the GAT increases behavioral health through quick assessment feedback. This perk allows soldiers to personally reflect on areas the GAT deems as weak. Peterson and various GAT creators think immediate evaluations are beneficial because they provide soldiers time to recognize and accept their results; this recognition proves valuable when soldiers attempt resilience behavioral transitions in later stages of the CSFP.

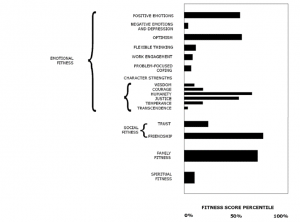

An example of a successful GAT synopsis on a male lieutenant using common military psychology vocabulary is shown below:

Figure 1, Peterson Christopher, A male lieutenant’s GAT synopsis from Christopher Peterson’s GAT analysis report, Assessment for the U.S. Army Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program: The Global Assessment Tool.

This GAT score report shows that this soldier tested well in trust, friendship, and optimism compared to other soldiers, but he lacked adaptability and problem-focused coping mechanisms. Thus, through the second prong of the CSFP, the Army will create a specialized online training module to improve the weaknesses this soldier has demonstrated.

The GAT was successful in predicting this lieutenant’s and many other soldiers’ potential to suffer from PTSD, depression, and substance abuse. Additionally, the GAT gauged how well soldiers would progress in the CSFP in terms of resilience and mental health. Many soldiers reported that the GAT was helpful in evaluating their current mental toughness standings. However, no data proves the test’s success in reanalyzing the progress, or lack of progress, of soldiers who followed specialized training plans. The GAT does not assess a soldier’s mental resilience in the long term.

Overall, results are inconclusive as to whether the GAT and the following online program do more than just point out a soldier’s mental flaws.

Fortunately, the third prong of the CSFP, the mental resilience training program, is a little more promising. The MRT program contains four modules. The first and second are focused on teaching the competencies that make up mental toughness and resilience. The third and fourth aim to strengthen soldiers’ social relationship skills and encourage character reflection.

James Griffith, a military psychologist, and his team gauged the success of the MRT through a questionnaire distributed to the Army National Guard. The questionnaire evaluated soldiers’ takeaways from the program. Soldiers reported that the MRT helped in improving self-assessed resilience and decreased behavioral health symptoms (symptoms known to be associated with suicide or depression). Peter Harm’s behavioral health evaluation, an evaluation not funded by the military, also reported that the MRT portion of the CSFP decreased mental health issues and substance abuse problems.

The fourth prong of the CSFP implements and measures the effectiveness of different resilience training programs. Each Army development school and battalion does not receive the same CSFP outlined training plan. Instead, most battalions receive and follow different tactical approaches for teaching resilience. Thus, small successes or failures from each specific program cannot be associated with the CSFP as a whole and cannot prove that this prong significantly develops soldiers’ mental resilience. However, with so many controlled resilience programs being tested on different battalions, the fourth prong of the program almost seems as though it’s turning our soldiers into guinea pigs for military psychologists to use as they please.

While certain aspects of CSFP, such as the Mental Resilience Training program, are beneficial in reducing the number of soldiers that suffer from mental health issues, no evidence suggests that the CSFP is a psychological breakthrough in increasing mental toughness.

Yes, the CSFP does help advance the field of military psychology; however, no one practice or module has been directly correlated with increased resilience. Furthermore, results showed the program’s failure to increase soldiers’ emotional buffer between a stressor and negative behavior. An emotional buffer is the delay between the brain’s recognition of the stressor and the resulting emotion. This emotional buffer is the “effective adaptation” in the resilience definition.

These negative implications of the CSFP don’t stop at largely ineffective mental resilience training. Many psychologists also ponder if the CSFP breached ethical conduct.

Psychologists from the American Psychology Association regard the CSFP as a research endeavor, not a legitimately tested program to increase resilience. According to Roy Eidelson, a distinguished social psychologist, the CSFP violates the Nuremberg code by not giving soldiers who were placed in this program informed consent. In his “Dark Side of the Comprehensive Fitness Program” report, Eidleson reprimands the CSFP for not hosting control trials before publishing and testing this program on one million soldiers. Moreover, Eidelson warns that such a push on mental toughness could cause soldiers to underestimate a potential threat, putting themselves and their comrades in further danger.

The magic formula for teaching mental resilience has not yet been cracked. Although programs such as the CSFP are under ethical scrutiny and devices such as the Halo Neuroscience headset haven’t shown transformative outcomes, they are still a step forward in the field of resilience research.

Who knows, with enough steps, maybe one day a daughter program of the CSFP or an advanced brain zapping headset will allow us to readily lug logs up and down a beach with only four hours of sleep.

By: N. Van Liew

References:

Casey, G. W., Jr. (2011). Comprehensive soldier fitness: A vision for psychological resilience in the U.S. Army. American Psychologist, 66(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021930

Eidelson, R., Pilisuk, M., & Soldz, S. (2011). The dark side of comprehensive soldier fitness. American Psychologist, 66(7), 643–644. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025272

Griffith, J., & West, C. (2013). Master Resilience Training and Its Relationship to Individual Well-Being and Stress Buffering Among Army National Guard Soldiers. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 40(2), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-013-9320-8

Harms, P. D. (2013). The Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness Program Evaluation. Report #4: Evaluation of Resilience Training and Mental and Behavioral Health Outcomes. Retrieved January 24, 2020, from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/pdharms/10/

Lester, P. B., Mcbride, S., Bliese, P. D., & Adler, A. B. (2011). Bringing science to bear: An empirical assessment of the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program. American Psychologist, 66(1), 77–81. https.//doi: 10.1037/a0022083

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Castro, C. A. (2011). Assessment for the U.S. Army Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program: The Global Assessment Tool. American Psychologist, 66(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021658

Image Credits:

Image 1: Smith Stew, Special Ops Prep for Log PT and Leg Stamina, Military.com, https://www.military.com/military-fitness/workouts/special-ops-prep-for-log-pt-and-leg-stamina

Image 2: Figure 1 op. cit. Peterson Christopher, Global Assessment Tool Report, Assessment for the U.S. Army Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program: The Global Assessment Tool.